According to OFFICIAL DATA, there has NEVER been an ‘immigration consensus’ in Canada in the past 30 years. Here is a deep dive into how this notion of a ‘consensus’ was sustained & how this indisputable reality was concealed.

POPULAR MISCONCEPTION

Over the last two years, as the debate on immigration – which has been taboo in Canada for the longest time – first became possible and then heated up, we have heard it said umpteen times that ‘Justin Trudeau broke Canada’s immigration consensus’. The merits or otherwise of the premise underlying the claim – that there was, in fact, such a consensus – haven’t been examined, at least to my knowledge, although I have seen many people disputing the notion on social media. However, their disputation is not backed by evidence and therefore is easily dismissed by the proponents of the ‘immigration consensus’ idea.

The latest iteration of the claim about Canada’s ‘immigration consensus’ that I came across was on the website of Without Diminishment, started by my X pals Alex Brown and Geoff Russ. The article by Peter Copeland begins with the sentence “The collapse of Canada’s once-strong immigration consensus has come with some stark lessons.” With utmost respect to my pals and to the work they are doing to bring non-MSM commentary to Canadians (including an article by yours truly), the question must be asked: Why hasn’t anyone delved into the reasons why this consensus (to the extent that one agrees that there was one) come into being? After all, we live in a universe of causality. For a phenomenon to exist, there must be factors that brought it into existence, and for the continuation of its existence for several decades. It is almost as if it is an article of faith that this consensus is the most natural state of Canadian society, one that does not need an explanation. As my regular readers know, I am wary of ‘self-evident truths’ and therefore decided to probe the question as to whether it holds up to scrutiny.

PROOF, PUDDING, ETC.

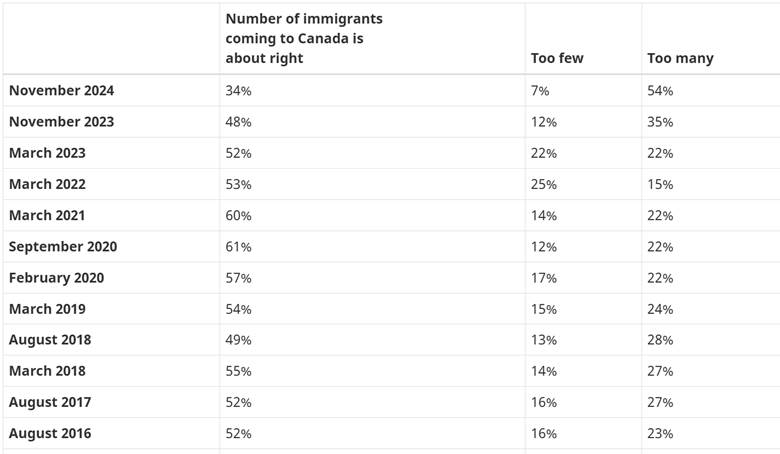

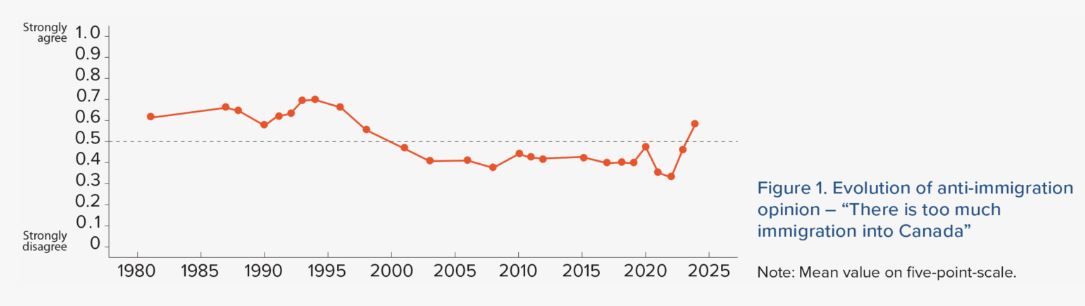

When I started probing, I was gobsmacked by what I found. Right there on the website of the government of Canada, there is evidence that an ‘immigration consensus’ has NEVER existed; barring brief periods when opposition to the immigration levels was relatively low, there has always been a robust percentage of Canadians who thought it was too high. Since the table of this data is too long, I have split it into 3 screenshots, so as not to sacrifice legibility (especially on mobile devices). Here is the link to the webpage: https://www.canada.ca/en/immigration-refugees-citizenship/corporate/transparency/transition-binders/minister-2025-05/public-opinion-research-canadians-attitudes-immigration.html (Note: I read this table from the bottom going up, so as to have a better understanding of how public opinion on this policy had changed over the years).

DEFINITIONS

In fairness, a consensus does not have to be unanimous; the Cambridge Dictionary defines the word as “a generally accepted opinion or decision among a group of people”, while the Merriam-Webster Dictionary says that the word means “(a) general agreement (as of opinion or fact) among a group of people or things or (b) the judgement arrived at by most of those concerned or (c) group solidarity in sentiment and belief”. Clearly, therefore, we are not looking for zero percent opposition to whatever immigration level there may have existed when the surveys were carried out; there needs to be a working definition of the phrases ‘generally accepted’, ‘general agreement’ and ‘most of those’ that these definitions use. There are two ways of looking at this, viz., the concept of a super-majority and the Pareto Distribution.

The latter one is more clear-cut: any percentage of disapproval (of any idea) at or above 20% would negate the contention that there is a consensus on the idea. As for a super-majority, I have encountered two views: either two-thirds of the total or three-fourths of the total. If we choose the former, then disapproval of the extant level of immigration at or above 33% would mean that there wasn’t a consensus, whereas by the latter metric, one would need only 25% or higher disapproval rate to say that a consensus did not exist.

I give you a choice: if you opt for the 33% super-majority model, out of 32 surveys, 12 had a disapproval rate of 33% or above, whereas for the 25% super-majority model, you have a whopping 24 surveys out of 32 with disapproval at 25% or higher, meaning that 75% of the time, there wasn’t an ‘immigration consensus’. Alternatively, if one opts for the Pareto distribution model, then almost all the surveys (30 out of 32) show disapproval rate of 20% or higher.

Out of these 3 metrics, which one should we prefer? My opinion is that as we have found out at great cost over the past 3 years as to the seriousness with which immigration impacts on society, the metric we choose to define ‘consensus’ in this policy area should be the most restrictive; only by ensuring the greatest buy-in from the ground level on this crucial policy (‘crucial’ as in being the crux of all policies) can we ensure that we have immigration levels that best serve Canada and Canadians, including the newcomers. Therefore, I choose the Pareto Distribution metric, by which there was hardly ever an ‘immigration consensus’ in Canada.

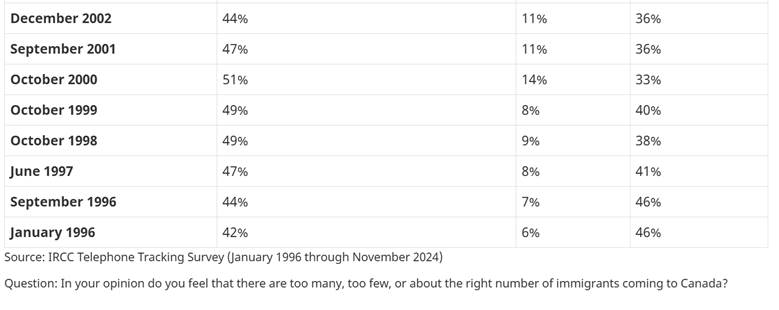

This is clearly NOT what has happened over the past 3 decades – which begs the question as to why. But before we delve into that, let us take a quick look at the in-depth study by IRPP’s Centre of Excellence on The Canadian Federation on changes in public opinion on immigration between 1995 and 2024 (see this link). Please note, the study uses data from 1980 onwards, so it covers a period of over 40 years. In other words, it gives an even broader view than the IRCC surveys. Using data from multiple studies, the report produces a highly illustrative chart (see below). Taking a value of 0.0 as representing the opinion that the respondents ‘strongly disagree’ with the question as to whether “There is too much immigration into Canada” and a value of 1.0 representing the opposite (i.e., the respondents agreed strongly that immigration was too high), the chart tells us the following:

The line above the value of 0.5 means that there was more agreement than disagreement that there was too much immigration in Canada. Even when it drops below 0.5, the line does not go significantly below that value. Even if one prefers either of the versions of the super-majority metric and not the Pareto Distribution, the definition of a ‘consensus’ is never met in this chart. And if one prefers the Pareto Distribution metric, it is a slam dunk that ‘immigration consensus’ is a myth.

LEADING INDICATOR

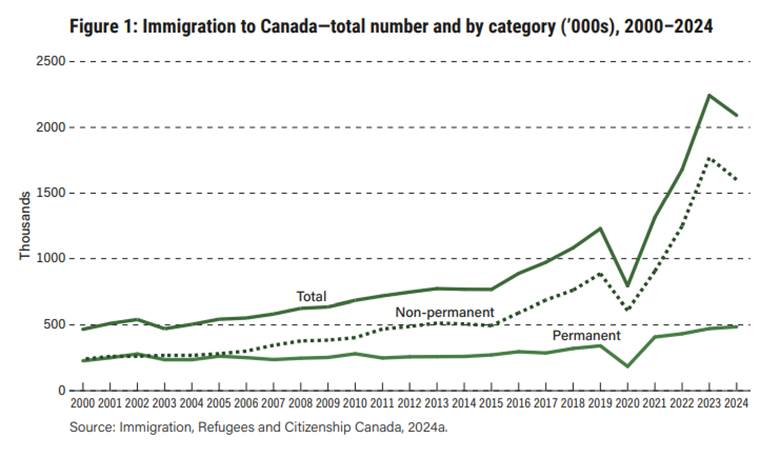

Now let us pay attention to the middle column in the above table, representing respondents who felt that the level of immigration that existed at the time of the survey was not enough. You will notice that it shows values above 20% on only two occasions, viz., March 2022 and March 2023 (25% and 22% respectively). In the remaining 30 surveys, the highest value is all the way back in December 2004, at 18%. The fact that immigration increased substantially – and if I am allowed to pass judgement, unsustainably – in ‘the Trudeau years’ indicates that this thin minority was propelling immigration policy in that period. This phenomenon is captured beautifully in the following graph in the recent report by the Fraser Institute, titled Canada’s Changing Immigration Patterns, 2000 – 2024 (see this link, page 11):

As you can see, while permanent immigration was relatively stable in the first 15 years of this century, non-permanent immigration was rising constantly in the same period, under the successive governments of Prime Ministers Chretien, Martin and Harper, such that before Justin Trudeau became Prime Minister, it had doubled in the preceding 15 years. As you can also see from the chart, PM Trudeau first turbocharged the rate of increase immediately on assuming office, and then put that turbocharge on steroids post-Covid. In my view, this was his defining mistake; the myth of an ‘immigration consensus’ wouldn’t have been dispelled, and he wouldn’t have earned the dubious distinction of having ‘broken’ that ‘consensus’ if he had continued on the trajectory that had been established by his 3 immediate predecessors. What I wrote in my earlier article ‘Immigration policy needs a DIFFERENT reset’, in the context of growth in real per capita GDP, healthcare and housing affordability applies equally here:

“Justin Trudeau’s folly was to turbocharge the process of deterioration that had already been afoot for over 4 decades before he became prime minister. Had he stayed the course and kept the policy on the ‘managed decline’ setting, he wouldn’t be seen by so many Canadians as the author of Canada’s multi-front misfortune that we find ourselves facing today.”

THREE FIG LEAFS

The above brings us back to the question that I posed earlier: How was the myth of an ‘immigration consensus’ not only maintained but also made its way into being the prevailing ‘received wisdom’, and that too for so long? After all, ALL the information that one needs to disprove the myth is out in the open, as yours truly has demonstrated in this piece. One supposes that as and when each of the studies, surveys and reports was published, it would have been covered in the media. AND YET, the fact that enough Canadians were opposed to whatever immigration level was existing at the time didn’t carry enough force for the powers-that-be to concede that the ‘consensus’ was a figment of imagination warrants an investigation.

I have tried to arrive at an answer to that vital question (‘vital’ in the sense that it supports life) – but that answer is long – roughly as long as this article is at this point, and that is already more than long enough. I mentally debated with myself as to whether I should (a) present the entire exploration of this issue in one article, which would place a greater demand on your time and attention or (b) split the exploration into two articles, and thus lose comprehensiveness in one place. On reflection, I concluded that respecting your time and energy took priority over my satisfaction of having all the content in one piece of writing. I will be posting my second article on this in a few days’ time (the rough draft is ready, but I will need to polish it up and maybe add some information / thoughts). But just to give you a hint, the 3 components of my answer are (a) expansive monetary and fiscal policies (b) an incurious / compliant commentariat and (c) immigration. Yes, I notice the irony: the myth of an ‘immigration consensus’ was propped up partly by immigration. With that tantalizing thought, I ask you again to await the Part-2 of this article.

***

Independent voices are more important than ever in today’s Canada. I am happy to add my voice to the public discussions on current issues & policy, and grateful for all the encouraging response from my listeners & readers. I do not believe in a Paywall model, so will not make access to my content subject to a payment.

To help me bring more content to you, please consider donating a small amount via this PayPal link on my website: https://darshanmaharaja.ca/donate/

Image Credit: Jeffrey Wynne via Wikimedia Commons; the image is at this link. Used without modification under Creative Commons License.